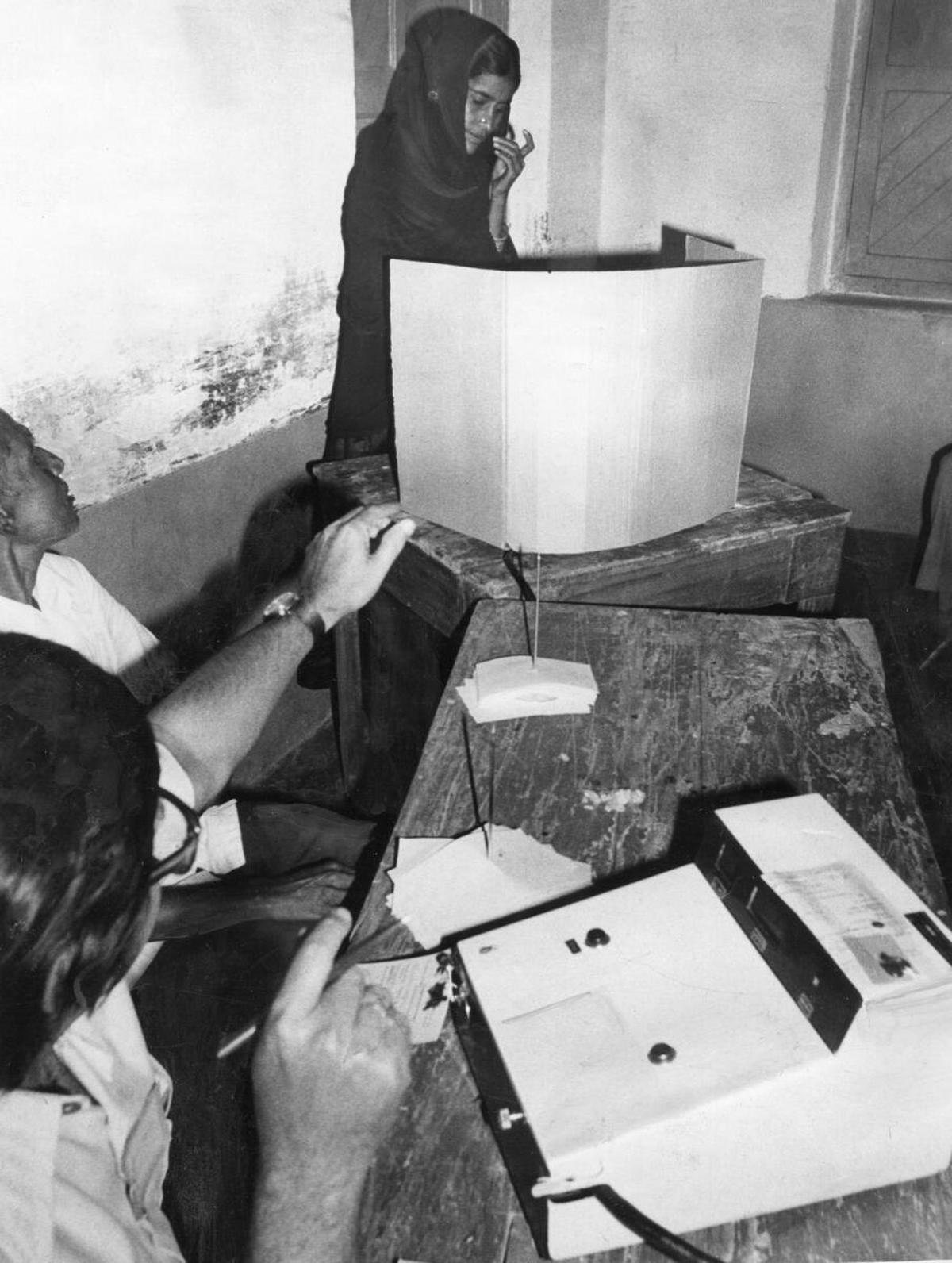

The story so far: In 1982, the township of Paravur caught national media attention. The Kerala constituency, heading to routine Assembly polls, was picked to experiment with a novel, more efficient way of voting. So far, India’s 35-crore-strong electorate used paper ballots; a medium that was tedious, time-consuming and became infamous for rigging and voter fraud. Paravur had a reputation for conducting peaceful elections, and here, the Election Commission conducted its trial: in 50 out of 123 booths, they replaced the traditional paper ballots with electronic voting machines. A controversy, repoll and reversal of the election verdict followed.

The experiment, however, changed the way Indians cast their vote today. Almost 55 lakh EVMs are expected to be in circulation in the upcoming Lok Sabha elections, set to commence on April 19.

The Electronic Voting Machine was pitched as an answer to a question of scale and security. The technology could simplify the electoral exercise that catered to a democracy of India’s size, and also eliminate voter tampering and manipulation. Over the decades, this solution has produced scepticism. Analysts and political leaders have questioned its transparency, reliability, and the value of a solution that seemingly reproduces similar problems.

A trial by technology

The transition away from paper ballots was spurred by a desire for convenience. The process was logistically laborious — involving the printing of millions of ballots, transporting and safely storing them, and physically counting hundreds of millions of votes. “Earlier there were lots of issues regarding sorting, tallying and bundling of ballot papers... We were amazed [at] the speed with which the EVMs declared results,’’ Congress leader P.C. Chacko told The Week in 2017.

The other concern was graver. By the late Fifties and early Sixties, India had begun to see the phenomenon of ‘booth capturing’: politicians or criminals would enter booths and forcibly cast votes in favour of particular candidates. The electoral exercise — a celebration of India’s post-Independence identity — became tainted with reports of violence and voter fraud, scholar Arvind Verma noted in a 2009 paper. He cited an instance from 1957, when “a group of upper-caste muscle-men chased away the electorate,” and several fraudulent activities across India which prevented genuine voters from exercising their rights. In Bihar, the 1967 elections laid bare the first organised efforts of booth capturing, and since then, “rigging and booth capturing started becoming facts of life,” wrote N.K. Saksena in his book India, Towards Anarchy, 1967 - 1992. The evil, “nominal in 1967,” started getting bigger with the nexus of politicians and police, and swept India, from Kashmir to Bihar and Bengal. In his book, Mr. Saksena recounts a score of efforts to check the movement of professional booth capturers and criminals.

There was growing consensus in the late Seventies to test the potential of the Electronic Voting Machine, a ‘blackbox software’ of sorts. The proposition came in 1977 from Chief Election Commissioner S.L. Shakdhar, according to The Week. A PSU called the Electronics Corporation of India Ltd (ECIL), Hyderabad, under the Department of Atomic Energy, developed a machine prototype in 1979.

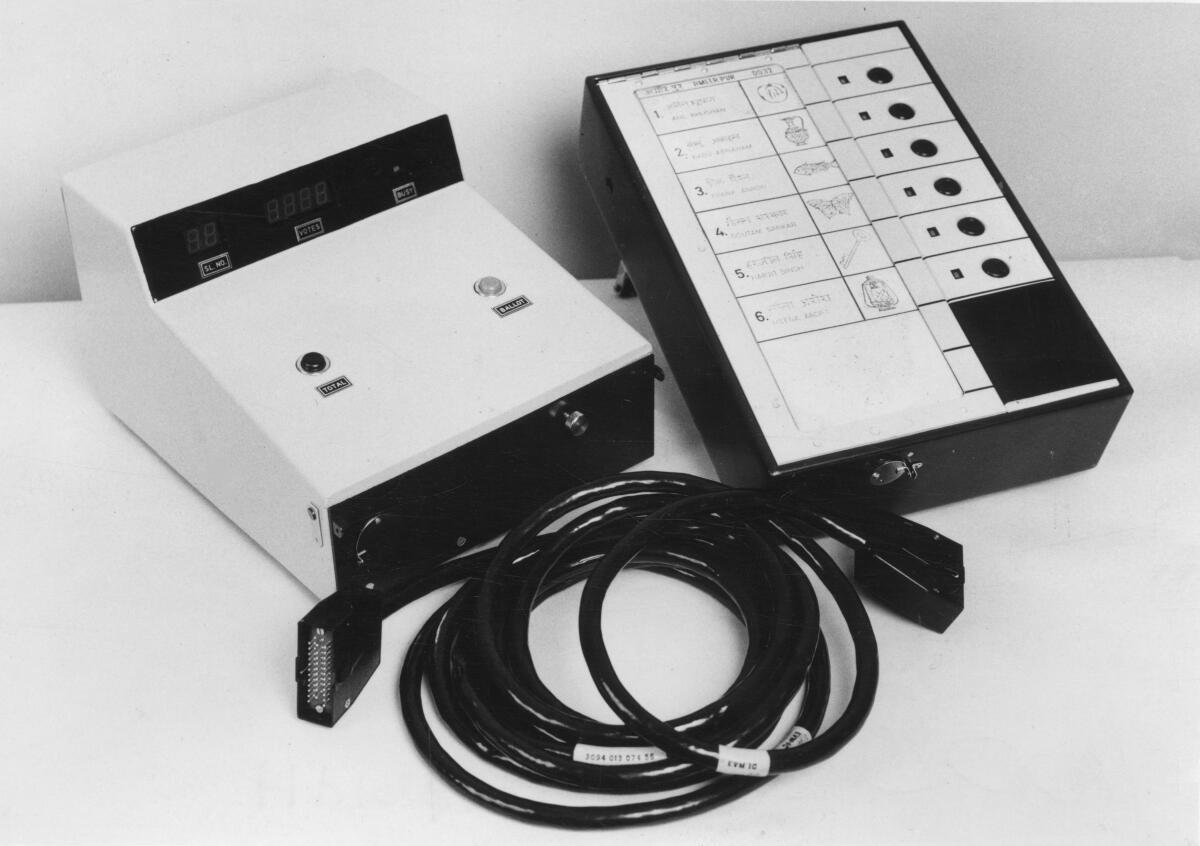

The two units of the BEL Electronic Voting Machine. On left is the control unit with the polling officer; on right is the balloting unit on which the voter casts his vote. Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

The industrial design of the EVM came from two IIT Bombay professors, A.G. Rao and Ravi Poovaiah. They were at the time also helping Bharat Electronics Limited with an electronic voting machine the company used for conducting their union elections. Crude and bulky, the model got a facelift after Mr. Rao and Mr. Poovaiah helped with “aesthetics,” as they recounted in a 2009 interview with The Times of India. “We went around the country to understand the nuances of an election from the perspective of a voter, the Election Commission as well as the parties in the race...That’s how it all began in the 1980s.” The duo developed a prototype which accommodated 16 candidates; it was merely 15 inches long and opened upwards (in the final design, the EVMs opened sidewards). Their design was called “nothing but a plastic suitcase.”

ECIL’s prototype was demonstrated before parties on August 6, 1980, and “after reaching a wide consensus,” the ECI issued directives under Article 324 of the Constitution of India for the use of EVMs, as per the ECI website.

Also Read | An electoral intervention that has clicked

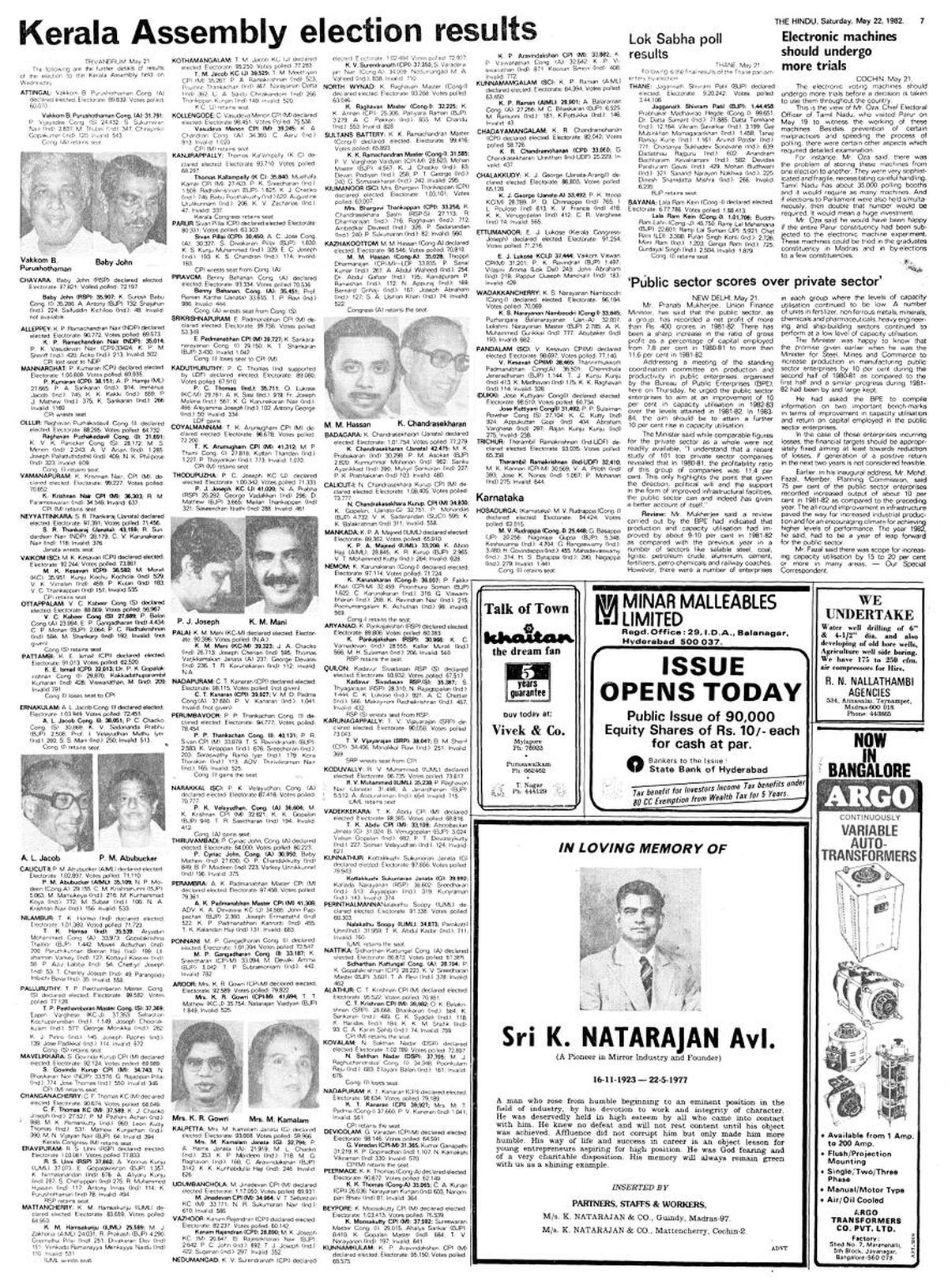

Then came the 1982 elections in Paravur, fought between the Congress leader A.C. Jose and the Communist Party of India leader N. Sivan Pillai. Mr. Pillai defeated the former by a margin of 123 votes, a result which Mr. Bose contested before the Kerala High Court and then the Supreme Court. He contended that the Representation of the People Act, 1951 and the Conduct of Elections Rules, 1961, did not empower the EC to use EVMs. The SC ordered a re-poll using conventional ballot papers, noting that the Commission could not ‘‘innovate a new method.” Mr. Bose eventually won the re-election.

Tamil Nadu’s Chief Electoral Officer at the time told The Hindu in a May 22 report “...besides prevention of certain malpractices and speeding the process of polling, there were certain other aspects [of EVMs] which required detailed examination.” Problems included the storage of these machines, “sophisticated and fragile,” from one election to the other, along with concerns about the investment. The Hindu in December 1982 also reported on another attempt to try EVMs in the January 1983 elections in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tripura.

An electronic machine broke down in a booth in Neelsandra due to snapping of wire but the polling official repaired it immediately and directed a voter to cast her vote at the Karnataka Assembly elections m Shantinagar (Reserved) constituency in Bangalore on January 05, 1983. Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

The door was not closed on EVMs. In December 1988, a section of the Representation of the People Act was amended and a new section, 61A, was included, empowering the EC to use EVMs. The amendment came into force on March 15, 1989. By this time, Bharat Electronics Ltd. was also chosen along with ECIL to manufacture the machines. The technology, however, was restricted for use in Lok Sabha and State Assembly elections.

The EVM works as an aggregator of votes in direct elections; press a button against the name of the chosen candidate, and the person with the maximum number of votes is declared winner. Presidential elections, or elections to the Rajya Sabha or State legislative councils, are based on proportional representation, where the elector marks preferences instead of exercising direct choice. A new EVM with a new technology would be required for this pursuit.

Lok Sabha elections debut

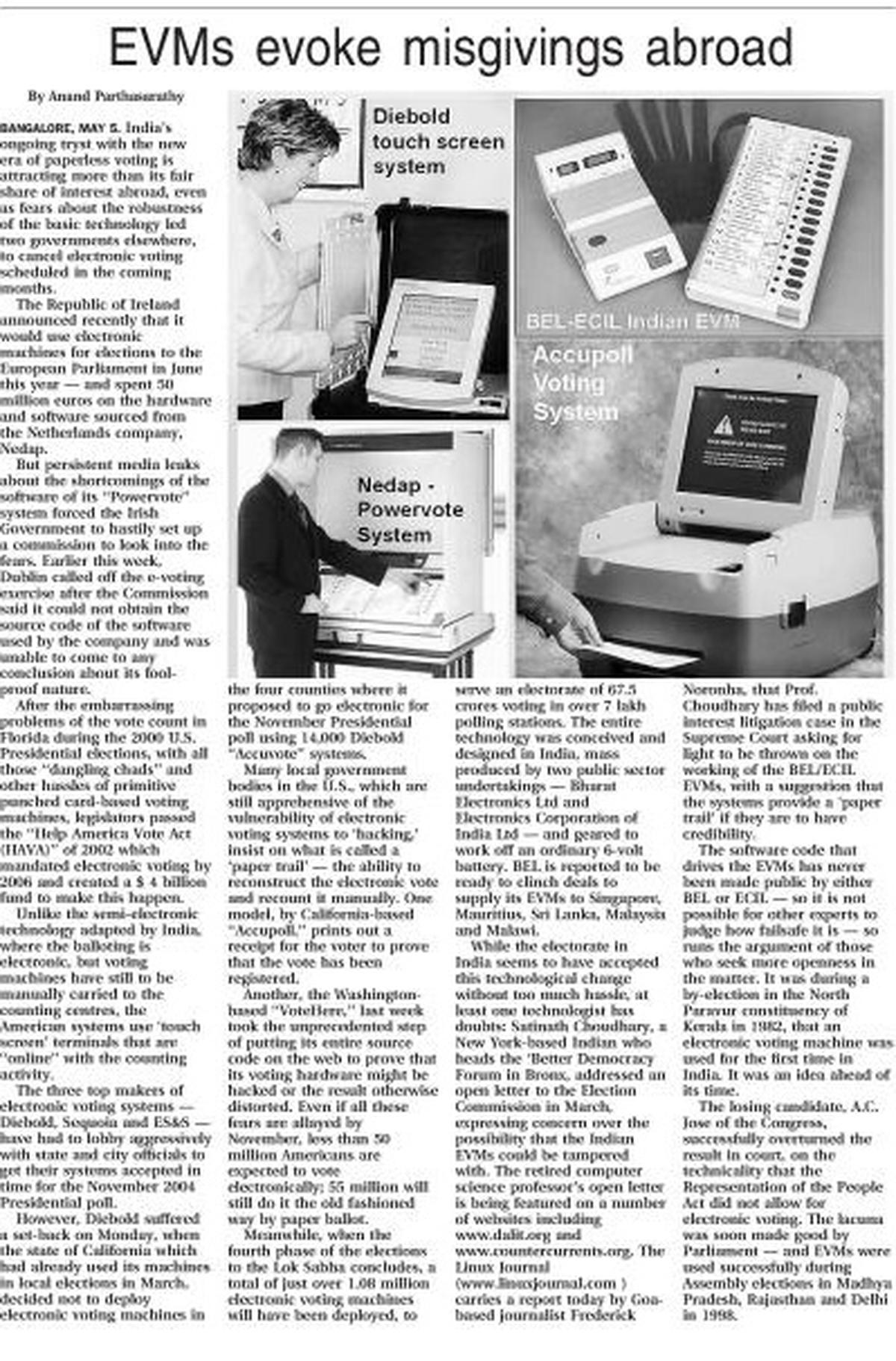

Chatter about the potential of the technology grew. In 1989, Congress leader Rajiv Gandhi, impressed with the machine, recommended that the technology be used in 150 constituencies in the 1989 General Elections, colonel H.S. Shankar told Business Standard in 2013. There was resistance, chiefly from Janata Dal leaders V.P. Singh and George Fernandes, who, in an infamous conference in October that year, proved that the EVM could produce faulty results. The Lok Sabha debut of EVMs was scrapped for the time being, but BEL still campaigned to prove the reliability of electronic voting.

The Indian Government instituted an Electoral Reforms Committee (ERC) in January 1990, which recommended a technical evaluation of the machine. The Technical Expert Committee was formed with S. Sampath of the Defence Research & Development Organisation (DRDO) in the lead. Early tests showed the EVMs were tamper-proof; the Sampath committee also conducted a mock election to substantiate its experiment, and “unanimously recommended the use of EVMs without any further loss of time marking it technically sound, secure and transparent,” the ECI noted.

R. V. S. Peri Sastry, Chief Election Commissioner of the time, reportedly discussed the findings with party heads who agreed on the use of EVMs in general elections. Between 1998 and 2001, the technology was used in 16 legislative assembly constituencies across Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Delhi; 46 parliamentary constituencies in 1999; 45 assembly constituencies in Haryana in 2000; and State assembly elections in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Puducherry and West Bengal in 2001. Their use was met with resistance in certain quarters; lawsuits before courts questioned their reliability and speculated about the avenues of fraud the EVMs could enable.

But the Supreme Court in the decisive 2002 case of Jayalalithaa and Ors vs. Election Commission of India stated on record: the use of EVMs in elections was constitutionally valid. The voting system replaced ballot papers fully in the 2004 Lok Sabha elections across all 543 parliamentary constituencies. A total of 10.75 lakh machines were in use. The Hindu in a May 13, 2004, report labelled them them the “Early Verdict Mechanism”— “...while they were not palatable to all, they ended the suspense for everyone,” with results declared in less than 12 hours from when voting commenced.

There were technical upgrades between 2001 and 2006. The lifecycle of EVMs is divided into three eras: M1 EVM (in use before 2006), M2 EVM (between 2006 and 2010) and M3 EVM (since 2013). The 2013 upgrade allowed the voter to pick the “None of the Above” (NOTA) option.

However, around this time, as EVMs gained ground in India, other countries that relied on electronic voting — including England, France, the Netherlands and the U.S. — banned their use. The German Supreme Court in March 2009 ruled that voting through EVM was unconstitutional.

A report in The Hindu published on May 6, 2004. Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

There was an obvious gap in the EVM, G.M. Sampath wrote in an earlier article for The Hindu. “An electronic display of the voter’s selection may not be the same as the vote stored electronically in the machine’s memory.” A cloud of mistrust loomed large over the EVM, with parties and analysts fearing the machines could be hacked or tampered with by miscreants. BJP’s L.K. Advani questioned the system in 2009 after the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance won a second term; the BJP and Shiv Sena in 2013 told the Election Commission that the machines could be manipulated to favour candidates. The issue of transparency, and the need for a paper trail, was articulated before the Supreme Court in the case of Subramanian Swamy v. Election Commission of India (2013). The Court ruled that “the paper trail is an indispensable requirement of free and fair elections,” and “the confidence of the voters in the EVM can be achieved only with the introduction of the paper trail.” [The judgment did not address questions of “technical integrity” of EVMs.]

Enter the Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT), introduced just six months before the 2014 General Elections. The VVPAT attached to the EVM produced a paper slip that allowed the voter to verify if their vote was cast correctly. The Conduct of Election Rules, 1961, were amended once again in 2013 to allow for VVPAT machines, which were piloted that year in the by-election for the Noksen assembly seat in Nagaland. This design solved “one-half” of the EVMs’ transparency and verifiability problem, wrote Mr. Sampath.

The 2019 General Elections were the first where EVMs were 100% backed by the VVPAT machine. Investigations later showed a mismatch in the number of votes polled and the final vote account— a claim denied by the Election Commission. One defence cited the machine’s technical strength: the machine has a software burnt into a one-time programmable (OTP) chip which could only be programmed once during the time of manufacture of these EVMs. This was proven wrong in 2019: an RTI reply by BEL showed that the OTP chips in EVMs can indeed be reprogrammed, according to The India Forum.

“Neither the EC nor the voter knows for sure what software is running in a particular EVM. One has to simply trust the manufacturer and the EC,” Mr. Sampath pointed out back in 2019. Curiously, the ECI does not directly control or supervise the BEL and ECIL. M.G. Devasahaya, a former IAS officer and coordinator of the Citizens Commission on Elections, wrote in The Wire that the manufacturersare under “the control of the respective ministries and the day-to-day administration is carried out by the board of directors packed with ruling Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) functionaries.”

The circular concern of security and transparency

The anatomy of today’s EVM includes at least one ballot unit, one control unit and one VVPAT. It is powered by a battery and self-contained, expected to have a shelf life of about 15 years. India-made EVMs have been imported to countries like Bhutan, Nepal and Namibia. A legal controversy erupted in Botswana in 2018 over the credibility and security of these machines.

A recommended addition to the machine which never materialised was the ‘totaliser.’ The ECI proposed this method in 2008 to solve for the issue of declaring booth-wise results. In the ballot paper era, paper slips were jumbled up for secrecy, to provide a degree of cover on how people voted in a polling station and prevent future intimidation. A parliamentary committee was set up in 2009 under the UPA-II government, but “it reached nowhere,” lawyer Kapil Sibal told The Wire last year. A 2015 Law Commission report backed the use of a totaliser: it would “increase the secrecy of votes during counting, thus preventing the disclosure of voting patterns and countering fears of intimidation and victimisation”.

In its four decades, the Indian EVM’s story comes full circle, returning to the point of mistrust and alleged electoral malpractice. A litany of legal disputes have been raised; some led to machine upgrades without addressing the integrity of the machine, and most of them were dismissed. In 2023, the Supreme Court refused to entertain a plea that called for an independent audit of the EVMs’ source code.

The most recent addition is the Supreme Court’s order to ECI, issued on April 1, calling for a detailed, 100% counting of VVPAT paper slips. So far, EC audited the machines by randomly checking VVPAT slips from five randomly selected polling stations per constituency, citing personnel limitations among other concerns. The sample size verified less than 2% of the machines, and would technically “fail to detect faulty EVMs 98-99% of the time,” former IAS officer K. Ashok Vardhan Shetty wrote in an essay. This is an “important first step” to ensure the integrity of the electoral process, the Congress said this week.

A parallel discourse emerges among politicians and civil society activists to return to the start: to use paper ballots, the “gold standard” for elections.

- The EVM works as an aggregator of votes in direct elections; press a button against the name of the chosen candidate, and the person with the maximum number of votes is declared winner.

- The anatomy of today’s EVM includes at least one ballot unit, one control unit and one VVPAT. It is powered by a battery and self-contained, expected to have a shelf life of about 15 years. India-made EVMs have been imported to countries like Bhutan, Nepal and Namibia.

- The most recent addition is the Supreme Court’s order to ECI, issued on April 1, calling for a detailed, 100% counting of VVPAT paper slips. So far, EC audited the machines by randomly checking VVPAT slips from five randomly selected polling stations per constituency, citing personnel limitations among other concerns.